Born: 26 February 1564

Died: 30 May 1593

Known for: writing plays about gay English kings, smoking tobacco as freely as he screwed the twinks of London AND spying for her majesty Queen Elizabeth I’s secret service

(10 mins)

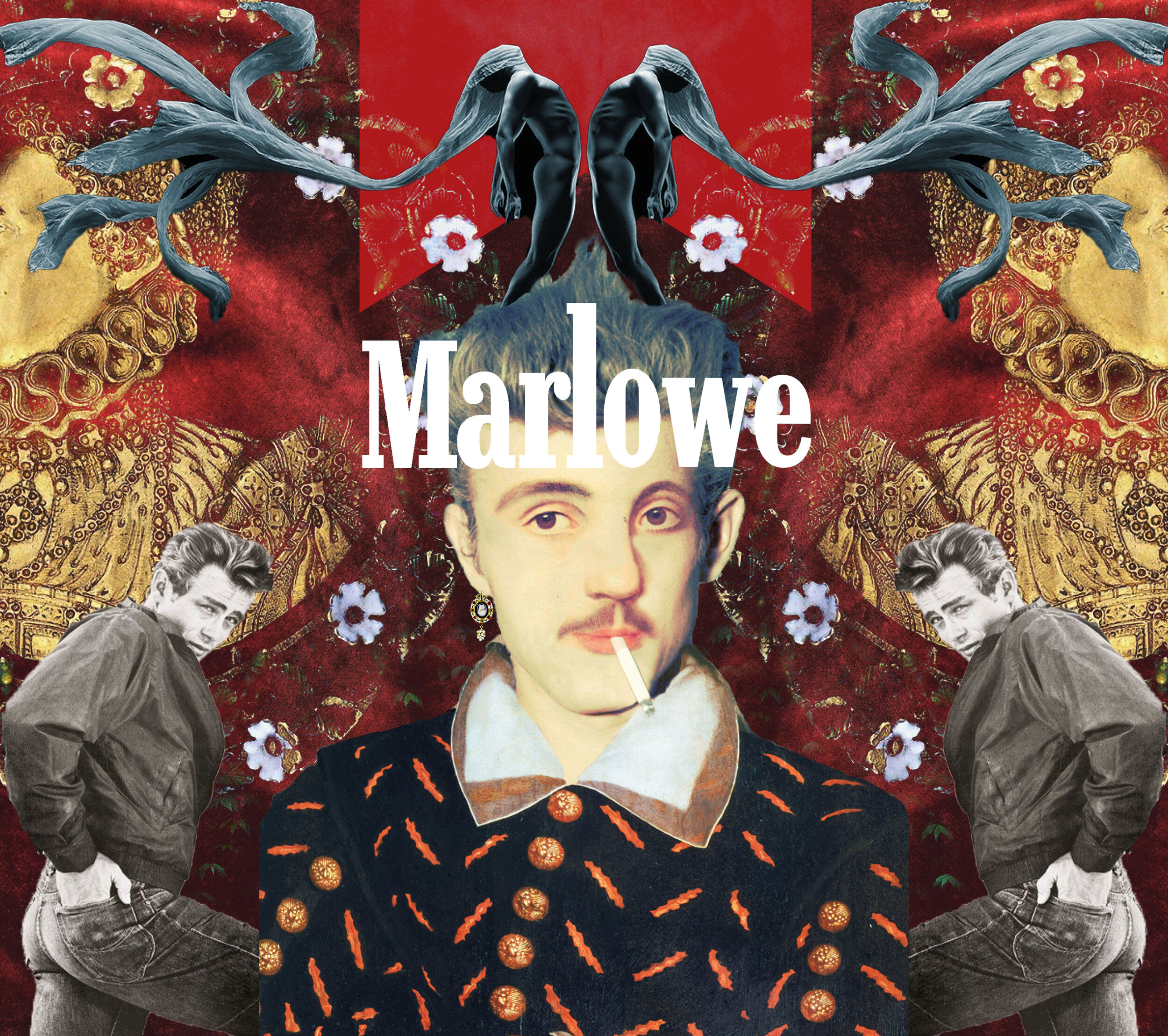

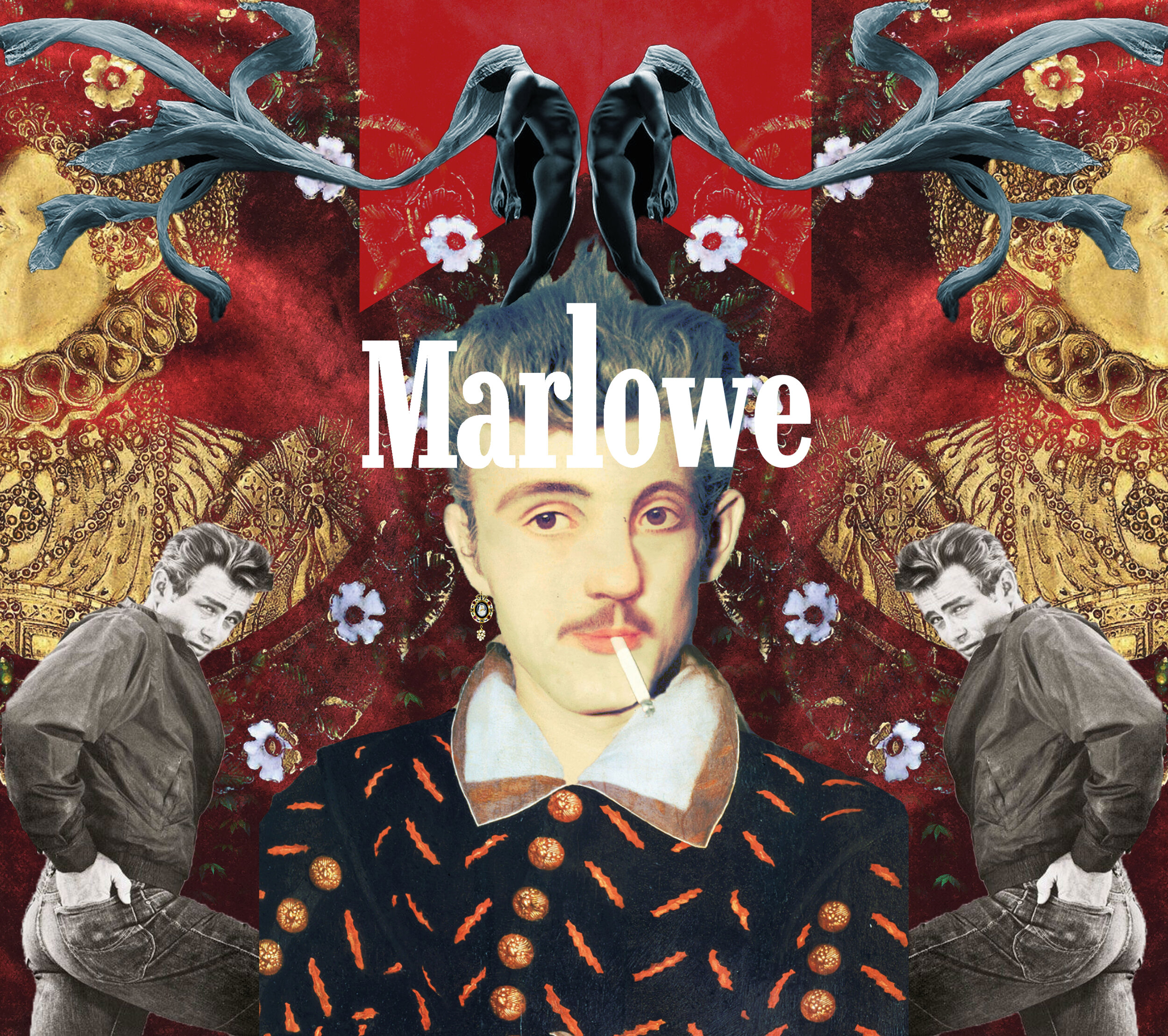

Christopher Marlowe. Poet, dramatist, spy. Alias: “Shakesqueer”. © Historical Homos 2020

Prologue: Marlowe’s Big Opening

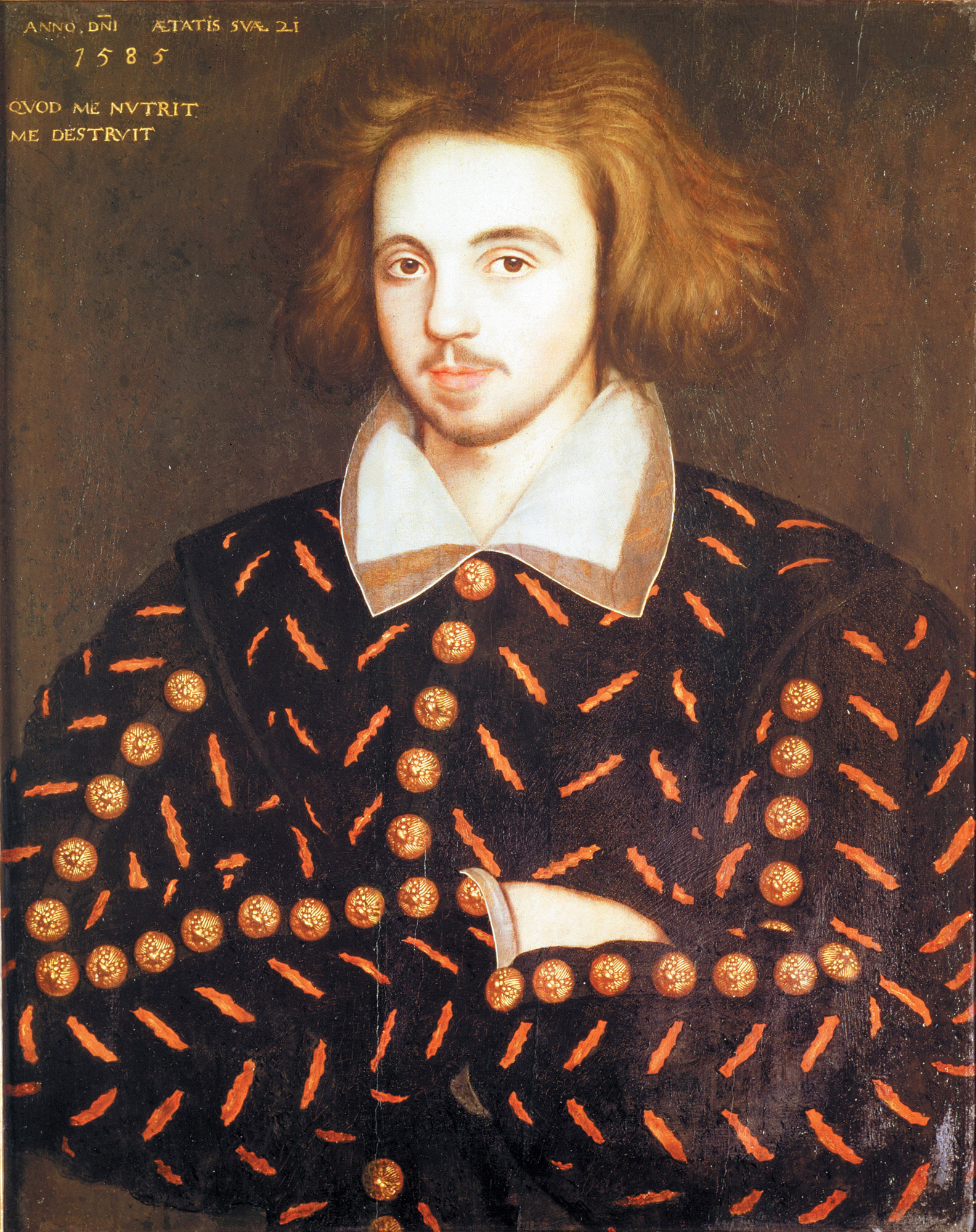

The only attributed portrait of Marlowe. No one knows if it’s him but look at that fabulous suit and that gay little face! (Wikimedia)

Christopher ‘Kit’ Marlowe was born into extremely unfabulous conditions:

the son of a shoemaker – but think your local cobbler, not Manolo

in Canterbury – so 60 miles east of anything fashionable in Elizabethan London

and the eldest of a low-class litter, living on their father’s debt and barrel after barrel of plague-laced beer.

Like any self-respecting Historical Homo, Kit wanted out.

And despite 50% infant mortality rates, he survived.

Kitty Kat even managed to get himself into the King’s School in Canterbury, while his father and younger sisters – ‘noisy and self-assertive’ – repeatedly got arrested for blaspheming and swearing in public.

The gorgeous King’s School in Canterbury, where Marlowe learned his ABCs. (via Hitched)

This rebelliousness seeped into Marlowe’s young mind — but there it mixed with a potent intellect and crucial skills.

You know, like literacy.

Eventually the two combined to propel him to the peaks of sublime poetry and radical philosophy that we read in his plays today.

But Marlowe didn’t stop at learning to read: he secured an Archbishop’s scholarship to the University of Cambridge around the age of 13, with the intention – he claimed – of pursuing a career in the totally heterosexual Church.

Corpus Christi College on a good day. Cambridge, England.

Like so many who’d cum before him (and after), Marlowe discovered himself at Cambridge. His studies at Corpus Christi College gave him a strong intellectual bent as a dramatist, and his mastery of Latin and Greek introduced him to the poetry of antiquity — particularly Ovid, the saucy author of the Amores (“Loves”), which Marlowe translated.

Mary, Queen of Scots. 1570s-80s. Always getting up in Elizabeth’s bidness. (Wikimedia)

Cambridge also alerted him to the subversive debates of the day: Catholic v. Protestant being the predominant scuttle-butt. But there were other theological debates (incomprehensibly) raging – like whether Jesus Christ was really divine or not – and Marlowe the Intellectual was almost certainly involved in them.

By 1584, when he received his BA, Queen Elizabeth had been busy getting herself into pickle after pickle:

Spain was lusting after her throne, trying to turn it Catholic again;

Mary Queen of Scots remained a captive, prickly thorn in her side, quietly supporting attempts on her life;

and plots from every Catholic corner of Europe threatened the stability of her Tudor monarchy.

Enter Marlowe the Spy.

Act I: On Her Majesty’s Secret Service

The Ermine Portrait, depicting Queen Elizabeth I around 1585. What a ferociously bad bitch. (Wikimedia)

Somewhere around 1584, Queen Eliza’s agents recruited Kit to spy on the closet Catholics at Cambridge.

They also apparently sent him on an all-expenses-paid trip to a Jesuit school in France (fun!) to spy on them some more.

It paid off: the Babington Plot to assassinate Elizabeth was uncovered in 1586, having originated at the Jesuit school in Rheims. (Leading to Liz finally growing the balls to chop Mary’s Scottish head off.)

Meanwhile, Marlowe picked up his MA degree at Cambridge and refused to take the cloth. Protestant or Catholic, Marlowe was having none of the religious life. He wanted to write.

So he took to London, the filthy, steaming epicenter of the Elizabethan stage, and started composing plays.

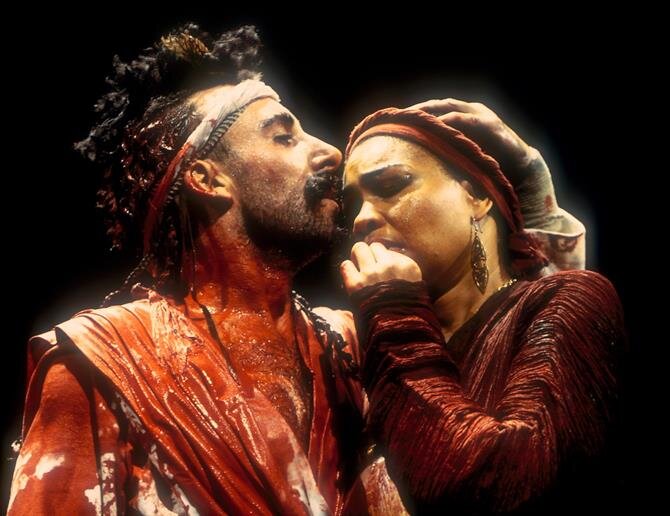

Antony Sher as Tamburlaine The Great, performed by the RSC in 1993. (RSC)

His earliest, Tamburlaine the Great, was a two-part hit about a lowly, conniving nobody who turns backstabbing conqueror in the Near East, seizing the throne of Persia and murdering his way to a tragic grave.

Like the very similar story of Keeping Up With The Kardashians, it was an instant hit.

Marlowe would go on to write some of the greatest and gayest plays London had ever seen — including Edward II, where a homosexual king gets himself and his boytoy Piers super, super murdered.

From 1587 to 1593, Marlowe wrote his gay little heart out — Tamburlaine, Dido Queen of Carthage, The Jew of Malta, The Massacre at Paris, Edward II, and Doctor Faustus were all completed in this short, intense period.

As a self-professed “messy bitch who lived for drama,” Marlowe’s career as a spymaster also continued to thrive.

“Anonymous Fag Amongst the Roses,” by Nicholas Hilliard. (Wikimedia)

He was often arrested and bailed out by Elizabeth’s higher-ups as a result. Big wigs like Lord Burghley, Francis Walsingham (the real spymaster) and Sir Christopher Hatton were among the lords keeping this rebel with too much cause out of prison.

By 1593, he was getting out of control. Rumors of his heretical views – in religion and sex – abounded, and an order for an investigation was issued while he worked on one of his gayest poems yet: Hero and Leander.

In late May of that year, with plague ravaging London for the 90 billionth time, Marlowe was invited to a house in Kent (SW England) to spend the day chilling, drinking and eating with two true scammers – Ingram Frizer and Nicholas Skeres – who were likely in the employ of Her Elizabethan Majesty’s Secret Service.

When the bill came, a brawl broke out, things were said that should not have been said and daggers were drawn.

At the age of just 29, the brilliant and boisterous Marlowe was penetrated to death just above his right eye — and not in the fun way.

Intermission: But Were He Gay?

“All they that love not tobacco and boys are fools.” This was one of Marlowe’s best known quips, recorded by one of the informants in the investigation against him. © Historical Homos 2020

There are two reasons we know Marlowe was gayer than Christmas:

His plays

The tea

This is England, so first we shall spill the tea.

It comes down to us mostly through the 1593 investigation Queen Elizabeth ordered into Marlowe’s private life, luckily preserved in many papers detailing his beliefs and boy-boinking proclivities.

One of the most famous quotes we get in these snitching papers is a quip that sounds too Marlowe to come from any lesser mind:

“All they that love not tobacco and boys are fools.”

All they with eyes and literacy can see this is scientific proof Christopher Marlowe was gay and also just very cool.

Leonardo’s St. John the Baptist, looking – admittedly – really gay. (Wikipedia)

But his informers continued: Marlowe had once declared that St. John the Evangelist “was bedfellow to Christ … [and] that [Christ] used [St. John] as the sinners of Sodoma”.

Another informer clarified what Marlowe meant: “Christ did love him with an extraordinary love.” In thinly veiled references to ancient Roman literature, it appears Marlowe was actually implying that St. John had played hungry bottom to Jesus Christ’s dom top!

This was pretty specific tea to be spilling about Marlowe.

Today, the powerful heterosexual lobby would have us believe that this evidence was biased (duh), as it was revealed by friends and informants who were out to build a case against Marlowe that his investigators wanted to hear.

But why such strong, musky scents of faggotry in this tea?

If we look at Kit Kat’s plays and poems, the plot thickens like a creamed Earl Grey.

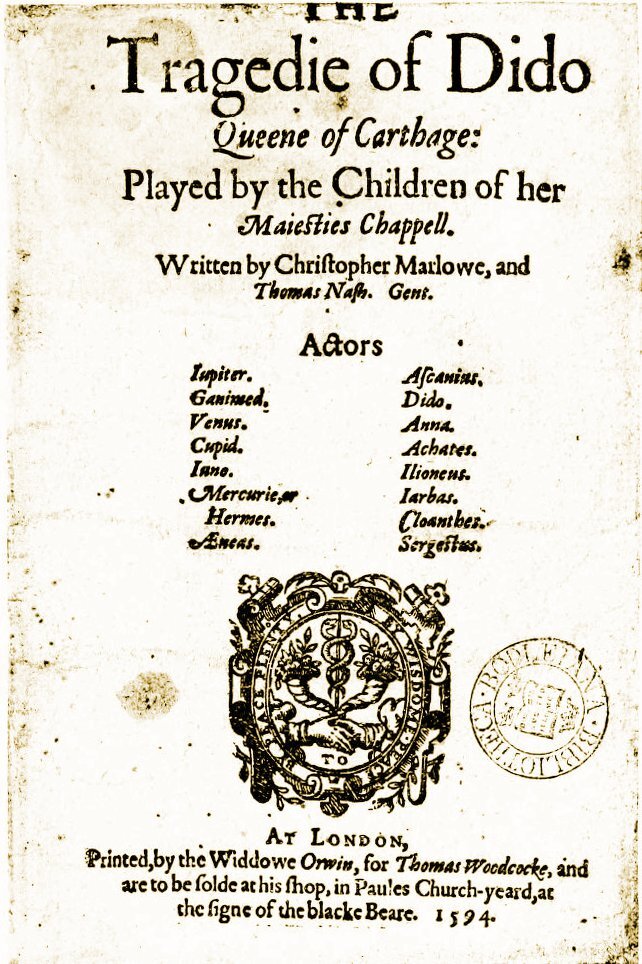

Frontispiece from an early edition of Dido, Queen of Carthage. 1594.

The plays positively abound with homosexual references and themes. This isn’t surprising, since Marlowe was obsessed with outsiders. As a poor boy from Poorsville, he probably felt he had much in common with them.

One of his earliest plays, Dido, Queen of Carthage, opens with Jupiter, king of the gods, dangling his boytoy Ganymede on his knee:

What is’t, sweet wag, I should deny thy youth?

Whose face reflects such pleasure to mine eyes?

The play was in fact written for the Children of Her Majesty’s Chapel, a troupe of teenage boys whose voices remained pleasantly pubescent.

This opening scene smells very queer indeed when we imagine Jupiter (probably played by an older boy) flirting with a beautiful younger boy on his lap, bedazzling him with women’s jewels and promising to protect him from his meddling bitch-wife, Juno — all in a play that has NOTHING to do with Ganymede!

Venus, telling off a very bored Jupiter, who just wants to get back to boning Ganymede. Abraham Janssens, c. 1613. (Wikimedia)

Now, the transvestite stage of Elizabethan England was a hazard of the trade – only boys could act on stage – and theater-goers wouldn’t have found it queer in itself. But they must have sensed the limit Marlowe was pushing when Venus arrives on the scene and confirms the gender-bending at work:

Aye, this is it; you can sit toying there,

And playing with that female wanton boy

While my Aeneas wanders on the seas

A beautifully dragged up Mark Rylance as Olivia in Shakespeare’s Twelfe Night. (GQ)

This was only the tip of Marlowe’s queer iceberg. He wrote another play about the contemporary St. Bartholomew’s Day Massacre in France (1572), when thousands of Huguenot Protestants were murdered by the ruling Catholic family of Catherine de’ Medici.

Henry III, who is crowned King of France after the Massacre in the play, was known IRL for his circle of “Mignons” (“cute boys” in French) whom he promoted and obsessed over during his short reign. They appear by name in the play and Catherine refers to their hold over Henry:

How likes your Grace my son’s pleasantness?

His mind, you see, runs on his minions

And all his heaven is to delight himself.

As in, delight himself all over their hot faces.

Act II: Climax! He Were Really Gay

Edward II, performed by the Lazarus Theatre Company in London, 2018.

Marlowe’s gayest play – by far – is Edward II, which follows King Edward II’s ascendancy to the medieval English throne and his disastrous promotion of Piers Gaveston, his favourite, at the expense of his French queen, Isabella.

At first, even the hetero noble (and future rebel) Mortimer indulges this love for Gaveston, citing a roll-call of classical queers in the King’s defense:

The mightiest kings have had their minions :

Great Alexander loved Hephestion;

The conquering Hercules for Hylas wept;

And for Patroclus stern Achilles drooped.

And not kings only, but the wisest men :

The Roman Tully loved Octavius,

Grave Socrates, wild Alcibiades…

Derek Jarman’s dope as fuck 1991 film adaptation of Edward II. (FanCarpet)

This flourish of fags was Marlowe’s way of introducing Edward II’s love as something comprehensible — admirable, even — to an Elizabethan stage.

But, like Maroon 5’s musical career, Edward II’s passion for Gaveston soon spirals out of control.

When asked by the nobles later in the play – who are forcing him to exile Gaveston – why he should love “him whom the world hates so,” the meek Edward can only reply:

Because he loves me more than all the world.

A still from the suggestive opening of Jarman’s Edward II (1991).

It seemeth the dick was just that good.

What’s most titillating about this play, though, is that Marlowe never describes Edward’s love for Gaveston in explicit sexual terms. Only the educated elite in his audience would have known that Edward II and Gaveston were renowned sodomites. (I bet MONEY Gaveston was IRL a renowned power bottom.)

Couched in ambivalent language, it’s unclear what we’re to make of their dramatized love, though Edward II seems pathetically weak – if somewhat noble-minded – and continually gets pushed around by his nobles onstage.

A stunning Tilda Swinton in Jarman’s Edward II, playing Queen Isabel. 1991.

Marlowe makes things even more complicated by painting Queen Isabella and her king-killing lover as just that: killers. They are imprisoned and/or murdered by the end of the show.

For any human heart leaving this play, it is Edward and Gaveston’s love that remains beautifully sticky in the mind. Their love is the tragedy.

Marlowe’s greatest poetry is reserved for the spectacle of their relationship, like when Gaveston describes how he plans to keep the new King Edward II interested in him by planning a fabulously gay party at court:

I must have wanton poets, pleasant wits,

Musicians, that with touching of a string

May draw the pliant king which way I please:

...

And in the day, when he shall walk abroad,

Like sylvan nymphs my pages shall be clad;

...

Sometime a lovely boy in Dian's shape,

With hair that gilds the water as it glides,

Crownets of pearl about his naked arms,

And in his sportful hands an olive-tree,

To hide those parts which men delight to see,

Shall bathe him in a spring;

…

Such things as these best please his Majesty.

GAY. Edward II, 1991.

Of course you can read the above as a perfectly hetero description of a scheming courtier.

OR you can read it as a scammy wanna-be queen titillating her prey with girly-looking boys in an ancient Greek cabaret.

You decide.

Epilogue: Marlowe’s Legasissy

Kit Marlowe was the Renaissance James Dean, a rebel with too much cause. © Historical Homos 2020

Marlowe wasn’t a “gay playwright” in his time — but he was gay and he did write important plays.

Both sides of his life are crucial for understanding the legacy of his life, especially as it was cut short and outshone by Shakespeare’s brighter star.

Here are a few things to remember this Historical Homo accomplished:

Marlowe rivalled, and some say bested, Shakespeare while he lived — the same Shakespeare who is the grand-zaddy of all English literature.

Marlowe innovated a theater of dark comedy, outsiders and the down-trodden for Elizabethan London — he put strange and alien people on stage, while refusing to hide his own perverted obsession with the homoerotic myths of antiquity, as well as his rejection of religious and sexual conventions.

Elizabeth I’s famous Rainbow Portrait, painted not long before her death in 1603. Her 50-year reign marked the end of the Elizabethan era. (Wikimedia)

Marlowe’s poetry is JUST as good as Shakespeare’s and sometimes even wittier (perhaps in the way only a vicious queen could be) — it celebrates male love and beauty with a sensuousness that Shakespeare never matched (though he did try in the Sonnets).

Marlowe rose from garbage-rags to become a highly educated, literary, scheming, brilliant and freethinking poet-dramatist: he wrote 6 plays in 6 years that we’re still reading and performing 4 centuries later.

Marlowe never got the chance to truly rival Shakespeare, but he was on the scene several years before him and probably regarded him as a friendly rival. His blank verse and innovative dramas paved the way for Shakespeare and others to do their best work.

That he was much more open about his counterculture beliefs in matters of religion and sex is easy to forget, but it’s precisely this rebel thinking that’s had such an impact on us today.

At the time of his death, Marlowe’s legacy was secured by the London glitterati who praised him as a luminary of English poetry, stamped out too soon. Shakespeare referenced him several times in As You Like It (~1598) and he continued to be imitated by poets who succeeded him. One of them put it quite lyrically:

Marlow, bathed in Thespian springs

Had in him those brave translunary things,

That the first Poets had, his raptures were

All air, and fire, which made his verses clear,

For that fine madness still he did retain,

Which rightly should possess a poet’s brain.

Another critic put it less glamorously:

Pity it is that wit so ill should dwell,

Wit lent from heaven, but vices sent from hell.

Derek Jarman’s 1991 Edward II was boldly queer in its portrayal of Marlowe’s sexually ambivalent play.

In the 20th century, Marlowe became something of a queer hero for artists because of his reputation as a rebel of the 27 Club variety – kind of like the bisexual James Dean, who openly flouted convention and got away with it because he was just too hot not to.

In the 1990s, Derek Jarman, pioneering director of New Queer Cinema, directed Edward II because of his affinity with the working-class queer hero that Marlowe represents today. The stark, gorgeous film bravely stages what the 16th century manuscript has always contained: crazy, deep love between two homos, fighting for legitimacy in a State that has no room for them.

Hero laments the dead Leander. Jan van den Hoecke, 1637. (Wikimedia)

But Kit Marlowe is more than just the Queer Shakespeare — he is a different animal, whose innovations in verse and on stage sounded the arrival of the Golden Age in Elizabethan literature. It’s not going too far to say that without this Historical Homo, we wouldn’t have had the same Shakespeare.

And in case you’re still on the fence – you heterosexual sympathizer – here are some quotes from Marlowe’s gayest poem Hero and Leander, which describes an ancient Greek hottie, Leander, seducing Hero (a confusingly named priestess of Aphrodite), whose poetic description consists mostly of her clothing and shoes. (Obviously a gay man’s perspective.) But first we get the dish on hunky Leander:

His dangling tresses, that were never shorn,

Had they been cut, and unto Colchos borne,

Would have allur'd the vent'rous youth of Greece

To hazard more than for the Golden Fleece.

…

His body was as straight as Circe's wand;

Jove might have sipped out nectar from his hand.

Even as delicious meat is to the taste,

So was his neck in touching, and surpassed

The white of Pelops' shoulder: I could tell ye,

How smooth his breast was, and how white his belly;

And whose immortal fingers did imprint

That heavenly path with many a curious dint

That runs along his back;

…

Some swore he was a maid in man's attire,

For in his looks were all that men desire,—

A pleasant smiling cheek, a speaking eye,

A brow for love to banquet royally;

And such as knew he was a man, would say,

"Leander, thou art made for amorous play”

The handsome young Earl of Southampton, c. 1590-3. Hero and Leander was almost certainly written in dedication to this beautiful youth. Shakespeare would (allegedly) address the lucky lad as well in Venus and Adonis. Attributed to John de Critz. (Wikimedia)

AND then when Leander swims across the sea to get to his lover, we get this delicious scene of the sea-god Neptune attempting to literally drown-fuck him as he braves the waves:

With that he [Leander] stripped him[self] to the ivory skin,

And crying, “Love I come,” leapt lively in.

Whereat the sapphire-visag'd god grew proud,

And made his capering Triton sound aloud,

Imagining that Ganymede, displeas'd,

Had left the heavens; therefore, on him he seiz'd –

Leander striv'd, the waves about him wound –

And pulled him to the bottom, where the ground

Was strew’d with pearl, and in low coral groves

Sweet singing Mermaids, sported with their loves

...

The lusty god embrac’d him, called him love,

And swore he never should return to Jove.

But when he knew it was not Ganymede,

...

He heav'd him up, and looking on his face,

Beat down the bold waves with his triple mace,

Which mounted up, intending to have kissed him,

And fell in drops like tears, because they missed him.

Leander, being up, began to swim,

And looking back, saw Neptune follow him.

...

The god put Helles bracelet on his arm,

And swore the sea should never do him harm.

He clapp’d his plump cheeks, with his tresses play’d,

And smiling wantonly, his love bewray’d [i.e. revealed].

He watched his arm, and as they opened wide,

At every stroke, betwixt them would he slide,

And steal a kiss, and then run out and dance,

And as he turned, cast many a lustful glance,

And threw him gaudy toys to please his eye,

And dive into the water, and there pry

Upon his breast, his thighs, and every limb,

And up again, and close beside him swim

And talk of love: Leander made reply,

“You are deceiv'd, I am no woman I.”

Earl of Southampton, aged 21. By Nicholas Hilliard. (Wikimedia)

I’m sorry, but you don’t write gorgeous poetry about clapping a young man’s “plump cheeks,” playing with his “tresses,” watching his “stroke,” buying him “gaudy toys,” stealing kisses, prying upon “his thighs” and “talking of LOVE” while you synchronize-swim together in ancient Greece unless you’ve sodomized a man.

I DON’T MAKE THE RULES.

Christopher Marlowe. Poet, dramatist, spy. Alias: “Shakesqueer”. © Historical Homos 2020

Further Reading

Bray, Alan. Homosexuality in Renaissance England. 1996.

Crompton, Louis. Homosexuality and Civilization. 2003.

Marlowe, Christopher. The Complete Plays. 2004.

Marlowe, Christopher. The Complete Poems. 2007.

Rowse, A.L. Homosexuals in History. 1977.

Ovid. The Erotic Poems. 1983.