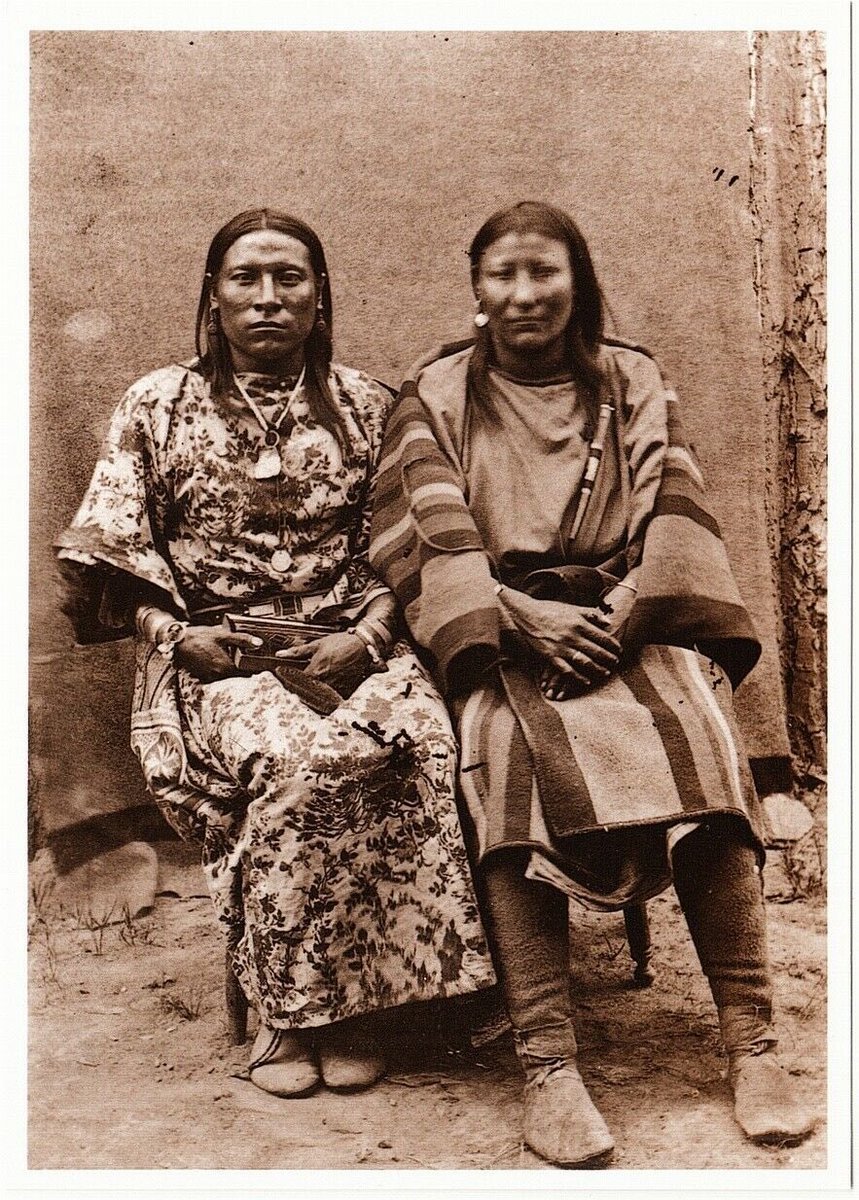

Osh-Tisch (left), whose name translates to “Finds Them and Kills Them,” was a Crow warrior, artist, and shaman who lived from 1854-1929. She was also a “badé,” a Crow word that historically referred to AMAB (Assigned Male At Birth) people who lived, worked, and dressed as women. Image via Whores of Yore (Twitter).

The colonization of Indigenous queer life

When European explorers and conquistadores first arrived in the Americas, they encountered no shortage of queer people in the continent’s indigenous tribes and empires.

Men who lived, dressed and worked as women were particularly common in the tribes of North America. Whereas in the Aztec empire that spanned Mexico and Central America, much harsher laws around male and female sexuality and gender identity appear to have been in place (at least in theory, if not always in practice). There is still plenty of evidence that homosexuality, lesbianism, and transvestism were known and named in these more southerly nations.

Already in the 16th and 17th centuries, Europeans condemned the “unnatural” sexual practices and identities they “discovered”. As more and more settlers, missionaries, and soldiers made their way through Indigenous territories, the reports of what we would today call queer or Two-Spirit people increased.

The French word berdache became particularly common to refer to individuals who were male-bodied and — for a variety of reasons — had chosen to live, work, and dress as women. Every tribe in North America had their own name for the berdaches. The Crow called them badé. The Cheyenne used the word hemaneh. The Lakota said winkté. All of these words typically referenced a fluidity of gender or an active desire to transgress it. (I’m only using the French word as a general catch-all to refer to this tradition across Indigenous nations, but keep in mind there was much variation and it is difficult to generalize.)

Detail from George Catlin’s Dance to the Berdash, 1835-1837, oil on canvas, Smithsonian American Art Museum. This was apparently an annual religious dance that honored the berdache(s) in the community.

A berdache’s femininity did not typically map onto Western ideas of binary gender identity. In many tribes, European observers remarked that the berdaches were taller and huskier than cis-gendered men. Many of them were also extremely skilled at hunting and soldiering, while also becoming expert in more traditionally feminine crafts like pottery and weaving.

One Jesuit missionary who traveled through French Canada in the 18th century attempted to explain this phenomenon in a chapter of his work titled “Men Who Dress as Women”:

If there are women with manly courage who prided themselves upon the profession of warrior, which seems to become men alone, there were also men cowardly enough to live as women. Among the Illinois, among the Sioux, in Louisiana, in Florida, and in Yucatan, there are young men who adopt the garb of women, and keep it all their lives. They believe they are honored by debasing themselves to all of women’s occupations; they never marry, they participate in all religious ceremonies, and this profession of an extraordinary life causes them to be regarded as people of a higher order, and above the common man.

From “Customs of the American Savages, Compared with the Customs of Ancient Times” (based on travels conducted in 1711-17) by Joseph François Lafitau

You can tell Lafitau had plenty of opinions about whether the berdaches were actually “people of a higher order” or not. His European, misogynistic worldview that “female” activity debased men was almost certainly not shared by most Indigenous communities who welcomed berdaches. But equally important is that his observation is echoed in many other sources: Indigenous communities seem to have attached a special status to the men (and occasional women) who transgressed their assigned genders and still operated as vital members of the religious, military, and artistic orders of their tribes.

The Europeans who first encountered the berdaches alternately believed them to be hermaphrodites, sodomites, or plain old moral degenerates. But the fact that the tradition of the berdaches persisted well into the 19th and early 20th centuries, as Indigenous populations were simultaneously systematically destroyed by encroaching Americans, demonstrates how important the institution was to many tribes.

We’Wha, a Zuni lhamana, works at a loom. “Lhamana” was the Zuni word for people assigned male at birth who lived as women. We’Wha was one of the most famous “berdaches” of her day, and even represented her people on an embassy to President Grover Cleveland in 1886.

Just like European colonists in earlier centuries, we cannot understand the berdaches along traditional Western conceptions of gender and sexuality. Their identities existed within an Indigenous matrix that acknowledged more than two genders. In fact, there is evidence that five fundamental gender identities were shared by many Indigenous tribes: male, female, Two-Spirit male, Two-Spirit female, and what we would today call transgender. Men and women who lived outside of their assigned gender’s boundaries were not always exclusively transgender, but sometimes they could be.

There was much more room for fluidity and ambiguity with Indigenous conceptions of gender — a hallmark of Native culture that Westerners eventually succeeded in diminishing almost to the point of total destruction.

One other source we have demonstrates the continued clash between Western ideals of gender and propriety and the ease with which Indigenous people flouted them. An American named John Tanner wrote an autobiographical account of his life with the Native peoples of Kentucky, who had captured him as a boy in 1790. He sometimes worked as an interpreter and lived much of his life according to Indigenous customs. In this excerpt he describes the arrival of a royal berdache to his lodge:

Some time in the course of this winter, there came to our lodge one of the sons of the celebrated Ojibbeway chief, called Wesh-ko-bug … . This man was one of those who make themselves women, and are called women by the Indians. There are several of this sort among most, if not all the Indian tribes; they are commonly called A-go-kwa … . This creature, called Ozaw-wen-dib (The Yellow Head), was now near fifty years old, and had lived with many husbands. I do not know whether she had seen me, or only heard of me, but she soon let me know she had come a long distance to see me, and with the hope of living with me. She often offered herself to me, but not being discouraged with one refusal, she repeated her disgusting advances until I was almost driven from the lodge.

Old Net-no-kwa was perfectly well acquainted with her character and only laughed at the embarrassment and shame which I evinced whenever she addressed me. She seemed rather to countenance and encourage the Yellow Head in remaining at our lodge. The latter was expert in the various employments of the women, to which all her time was given. At length, despairing of success in her addresses to me, or being too much pinched by hunger, which was commonly felt in our lodge, she disappeared, and was absent three or four days. I began to hope I should be no more troubled with her, when she came back loaded with dry meat. She stated that she had found the band of Wa-ge-to-tah-gun, and that that chief had sent by her an invitation for us to join him. …

[B]efore night the next day, we arrived at Wa-ge-to-te’s lodge, where we ate as much as we wished. Here also, I found myself relieved from the persecutions of the A-go-kwa, which had become intolerable. Wa-ge-tote, who had two wives, married her. This introduction of a new inmate into the family of Wa-ge-tote occasioned some laughter and produced some ludicrous incidents, but was attended with less uneasiness and quarreling than would have been the bringing in of a new wife of the female sex.

from John Tanner’s “A Narrative of the Captivity and Adventures of John Tanner, U.S. Interpreter at the Sault de Saint Marie, During Thirty Years Residence among the Indians,” 1830, p. 105-6.

This is such a fascinating excerpt because Tanner, who is writing for an Anglo-American, white audience that shared his prejudices, clearly takes pains to demonstrate how “disgusted” he is by the 50-year-old berdache and her advances. He wants his audience to know that even though he lived with Indigenous communities most of his life, he doesn’t share their moral worldview. But at the same time, the story reveals how the status of the berdache allowed her to seek shelter in various families, without causing disruption to the other kinship networks established by additional wives. Even at 50, she was still a desirable marriage prospect for Indigenous men.

We also see genuine respect for the expertise of Ozaw-wen-dib in hunting, tracking, and of course the “various employments of women.” We have to read between the lines of this source, but when we do, it becomes clear just how multidimensional the lives of the berdaches must have been.

Lukas Avendaño’s “Lukas y José ” (2017). Photo: Mario Patiño. Image via New York Times.

In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, European and American missionaries attempted to stamp out the tradition of the berdache. And many Indigenous communities in the 20th century became hostile toward queer people and identities in their communities.

Thankfully this has changed a great deal in the past several decades, and there is now widespread acknowledgement of the importance and sanctity of Two-Spirit identities — a term that obviously refers to the duality of genders at play in us all.

Re-writing history from an Indigenous perspective is not only fascinating in its own right — who knew there was a sacred gender nonconforming role for people in Native American tribes?! — it’s also a fantastic way to resist the Eurocentric readings of history we all grew up with.

And particularly in America, where the myths of Manifest Destiny and the Founding Fathers continue to obscure the violent, treacherous history of nation “building” we all must reckon with. Nation-building always entails a cost of nation-destroying, and the memories of the people who resisted — particularly the queer people who stuck to their traditions — deserve to be kept vividly alive.

Sources

https://indiancountrytoday.com/archive/two-spirits-one-heart-five-genders

https://www.kqed.org/arts/13845330/5-two-spirit-heroes-who-paved-the-way-for-todays-native-lgbtq-community

Katz, Jonathan. “Gay American History: Lesbians and Gay Men in the U.S.A.” 1976.